Artigos | Articles

Phrourion and coins in Central Sicily (6th-3rd Century BCE)1

O Phourion e a moeda na Sicília Central (VI-III séc. a.C.)

Phrourion and coins in Central Sicily (6th-3rd Century BCE)1

Classica - Revista Brasileira de Estudos Clássicos, vol. 34, núm. 1, pp. 11-30, 2021

Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Clássicos

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional.

Recepción: 29 Octubre 2019

Aprobación: 12 Febrero 2020

Abstract: Since its appearance, the minted coin has been an indicator of Greek presence in the Ancient Mediterranean. Despite being a revolutionary notion in the economy of the ancient world, the adoption of the monetary system was not always unanimous, especially among indigenous peoples outside the Hellenic context. This dissension happened because coins, besides the intrinsic value in the metal of which they are made, carry symbolic values intimately linked to the society that produced them. The presence or absence of coins in certain archaeological contexts informs us of their reception among native communities. These objects, accepted by external consumers in adopting them to their everyday life or rituals, were thus also accepted in that they were given new meanings. The case of Sikan phrouria in central Sicily is quite interesting. The circulation of Greek coins was scarce in this territory. Its intensity, however, varied over time, and space. These differences allow us to observe the social changes that occurred in Sikan communities between the 6th and 3rd centuries BCE, as well as to understand coins as active agents in cultural transformation. The contextual material analysis carried out in this paper focuses on the different perceptions of Economy among Greeks and Sikans. The latter showed, in turn, a certain resistance to coins, favouring more traditional forms of exchange.

Keywords: Ancient Mediterranean, Greek numismatic, Sikan Phrourion towns, economy and identity, agency of coins.

Resumo: Desde o seu surgimento, a moeda cunhada tem sido um indicador da presença grega no Mediterrâneo antigo. Apesar de ser uma ideia revolucionária na economia do mundo antigo, a adoção do sistema monetário nem sempre foi unânime, principalmente entre os povos indígenas fora do contexto helênico. Essa discrepância ocorreu porque a moeda, além de seu valor intrínseco devido ao metal de que é feita, carrega valores simbólicos intimamente ligados à sociedade que a produziu. A presença ou ausência de moedas em certos contextos arqueológicos nos informa, portanto, de sua recepção entre as comunidades nativas, que aceitavam objetos de consumo externos adotando-os no cotidiano ou nos rituais e carregando-os de novos significados. O caso dos frúria sicânios, no centro da Sicília, é muito interessante. Nesse território, a circulação de moedas gregas era escassa, mas sua intensidade variava ao longo do tempo e do espaço. Essas diferenças nos permitem observar as mudanças sociais nas comunidades sicânias entre os séculos VI e III a.C. e entender as moedas como agentes ativos na transformação cultural. A análise do material contextual realizada neste trabalho enfoca as diferentes percepções da economia entre gregos e sicânios, que mostraram certa resistência à moeda, favorecendo formas de troca mais tradicionais.

Palavras-chave: Mediterrâneo antigo, numismática grega, Frúrion da Sicania, economia e identidade, agência da moeda.

Introduction

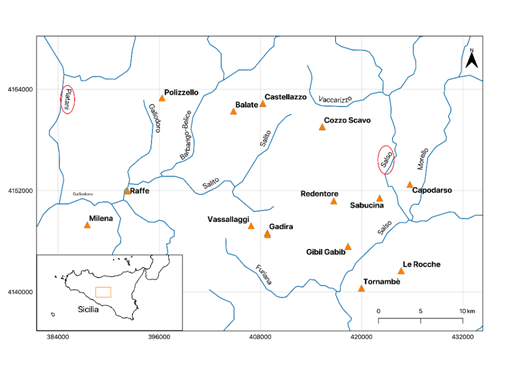

This paper will discuss the impact caused by the introduction of coins in the inner territory of Sicily with the provision of certain case studies. The analyzed territory comprises the area between the middle valley of the Salso River and the middle valley of the Platani River (Fig. 1), a territory that once belonged to Ancient Sikania. From the 7th century2 towards, the Greek apoikoi from Gela and Akragas extended their chorai towards the interior of Sicily and encountered communities inhabiting this region since the Neolithic era. Interactions between Greeks and non-Greeks in this area occurred in different forms and degrees, depending on the economic and political circumstances that characterized the history of Sicily between the Archaic and Hellenistic periods (6th-4th centuries) (Miccichè, 2011).

To observe this phenomenon, we usually resort to written and material sources. In the case of Central Sicily, however, written sources are extremely rare. The territory examined in this paper is quite absent from textual sources. The written tradition on non-Greek populations is a Greek construction which therefore reflects a view that is not always objective and sometimes laden with a certain prejudice – a topos constituted in Greek culture that must not be neglected when working with textual sources (Gazzano, 2009). Historians and archaeologists invite us to reflect on the difficulty of relying solely on textual or material sources. As Pancucci (2006, p. 109 ff.) points out, when only relying on textual sources, the risk is to reconstruct a history filtered by an interpretive model – shaped by Greek historians – applied to a world already distant in time and “nebulous in fact”. Regarding material sources interpreted by archaeologists, we cannot always account for the various factors that led to the formation of certain contexts nor escape modern conditionings. Accordingly, Albanese Procelli (2003a, p. 23) states that it is insidious to identify ‘cultures’ (phases) with ethne (Antonaccio, 2004, p. 61). Ancient textual sources with their Hellenocentric point of view were in general not interested in the history of pre-Hellenic peoples (Anello, 1997, p. 539; Galvagno, 2006, p. 28; Miccichè, 2011, p. 24) and therefore reported manipulated information at times. However, both textual and material sources,5 while providing some challenges to interpretation, are fundamental allies that help scholars put together the pieces of the variegated puzzle of ancient Sicily and its inhabitants. For example, among the cities here considered, only Mytistraton – cited by Diodorus Siculus (XXIII, 9, 3) and other sources (see Hansen; Nielsen, 2004, p. 217) – was correctly identified in Monte Castellazzo di Marianopoli, thanks to numismatic and epigraphic evidences (Sole, 2012, p. 96-126; Manganaro, 1964, p. 436). It is hard to determine the name of other indigenous towns (without specifying their location), since we only have the written source to state definitive attributions. This is the case of Motyon, which was cited by Diodorus (XI, 91, 4) as a phrourion under the control of Akragas: many scholars have ventured into trying to attribute this name to the town Vassallaggi or the one in Sabucina, without ever reaching a conclusion.6

Artefacts are therefore essential for reading social dynamics. Particularly coins have a special condition among the items of material culture: they carry a range of meanings that result from the intrinsic value of the metal itself and from the representative value of identity and power of the issuing city as well as they play a role as mediators of spiritual and material values. For this reason, they are among the several objects that are present in sacred spaces (such as temple offerings or grave goods in the necropolises) and in quotidian contexts (such as abandoned goods in homes or lost in places of negotiation).

The coin, as a metallic disk bearing signs and symbols, originated and was diffused in the Greek world in the 7th century.7Before its invention in the Mediterranean context, some forms of coins consisted of precious metals (bronze, silver, gold and electro) and were weighed following established standards (Howgego, 2002, p. 15) to be cut and forged into ingots or instruments. Coins represented a revolutionary technological innovation in that they enabled agile handling of value and exchange: their size facilitated the transportation of metal with purchasing power; their weight and types established a universal language in transactions; and the officiality was guaranteed by the authority that produced it, conferring beyond a real value a nominal value. That is why the coin became the most accepted form of money over the centuries. Nevertheless, it has not always been this way.

In the case of Sikania, between the 6th and 4th centuries, coins did not exist in the main and were apparently rejected by the local people who ran their own economy differently from the Greeks. Even so, the documentation shows a preponderant presence of coins from Akragas and Syracuse between the 5th and 4th centuries, revealing the importance of this territory for both poleis at that time. Coins can therefore have an important role in the construction of identity. Recognizing the ability of coins to convey identity values helps to understand the social changes that occurred throughout the period in which Greeks settled on Sicily: after an initial phase of apparent rejection of the Greek monetary system by the indigenous population (between the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 5th centuries), coins began to have a larger circulation between the 5th and 4th centuries, when the division between Greeks and non-Greeks was weakened.

Coins in Sikania

Metallurgical production in Sicily is known to have begun as early as the second half of the 4th millennium BCE. The oldest material attestation is a melting furnace fragment found in Lipara (Giardino, 1997, p. 405). It was, however, mainly in late Bronze Age that metallurgy reached quite an advanced technological state, as can be seen from the presence of sets of metal objects (mainly bronze) throughout the island, which demonstrates the growing specialization in this production. At this time, metals gained a significant economic value. In Lipara, for example, a hoard of bronze objects weighing 75kg was found inside the city walls, which is a sign of integration of metallurgy and its artisans within the social structure (Giardino, 1997, p. 409). The increase in production, especially in the end of the Bronze Age, was surely linked to the progress in agriculture, logging and cattle raising, which also meant a definition in social stratification (Albanese Procelli, 2003b, p. 11).

Sets of bronze objects were found both in Sabucina and in Polizzello (Albanese Procelli, 2003b). In metallurgical production, on top of the raw materials of local origin, artisans resorted to melt ingots and discarded bronze objects. Bronze assemblies and intentional fractures in ingots and objects reveal the need to dispose of metal quickly, either for the production of tools, vessels and jewellery or as a good of trade (Sole, 2009). Although metal, in its raw or worked form, was considered an object of barter, there are no apparent weighted reference values, resulting in the fact that we cannot conjecture a predetermined system of exchange (Albanese Procelli, 2003a, p. 95). Metal in the late Bronze and Iron ages on Sicily had therefore no value as a standardized instrument of exchange – a concept that was later introduced by the Greeks in the 6th century with the issuing of coins.

Before entering the discussion on coins and their role in Central Sicily, it is necessary to clarify the meaning of phrourion in this article. In classical sources, phrourion is a fortress that houses soldiers with the purpose to protect borders or critical areas of the chora (Winter, 1971, p. 42-3; Fredericksen, 2011, p. 13-5). Be that as it may, I am using phrourion in the same manner as Diodorus Siculus, that is, as that which names the ancient indigenous towns on Sicily, inhabited mostly by Sikel and Sikan communities. This use is also widespread among Sicilian scholars.8

The data in this study come from a group of ancient indigenous Sikan cities in a territory between the middle valley of the Salso River and the middle valley of the Platani River, that is, in the very core of Sicily (Fig. 1) called Mesogeia.

Figure 1

Hydrographic map of Central Sicily between the Salso River (right) and the Platani River (left). The area is crossed by streams nearby where the surveyed archaeological sites are distributed. Credit: Javier Ruiz-Perez.

The basis of the numismatic survey conducted in this research is Lavinia Sole’s monograph Gli Indigeni e la moneta. Rinvenimenti monetali e associazioni contestuali dai centri dell’entroterra siciliano (2012). This work encloses a detailed catalogue of coins found at the archaeological sites of Central Sicily, especially the ones in the territory of Caltanissetta district. In this text, the numismatic record can be 1) contextual, i.e., coming from excavations; 2) sporadic, as being found on the surface during a visit or other contingencies; 3) from hoards.

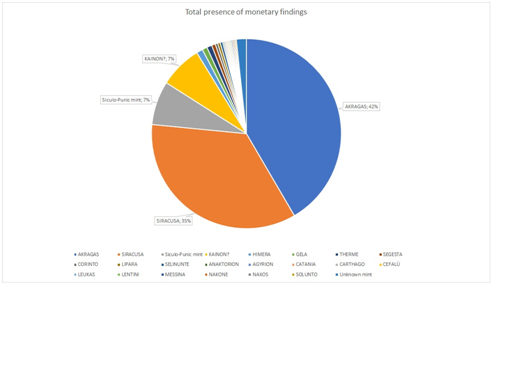

The data presented here is divided into “hoards” (when available) and “monetary findings”. A brief commentary on data from hoards is necessary. Coin hoards do not necessarily reflect the reality of the coins in circulation, depending on the very nature of the hoard as an archaeological document. Sets of coins intended for the accumulation of money of a particular intrinsic value bring together specimens from different times and places. It is not always know how or why such sets were formed. Nor can we know who lost or buried them – perhaps members of the community who, in an emergency, had to hide their money, or passing visitors who, for unknown reasons, had to dispose of the money they were carrying with them (Stazio, 1983b, p. 68; Florenzano, 1988; Grandjean, 2015, p. 6). In order to visualize the temporal distribution of coins and their origin, the available data has here been organised and a synoptic graphics created.The first diagram (chart 1) shows the presence of the mints that make up the numismatic data of the research territory. The highest percentages are represented by the Akragantine (42%, 195 coins) and Syracusan (35%, 164 coins) coins, followed by Siculo-Punic Mints (7%, 35 coins) and KAINON (7%, 34 coins).

Chart 1

Total presence of monetary findings.

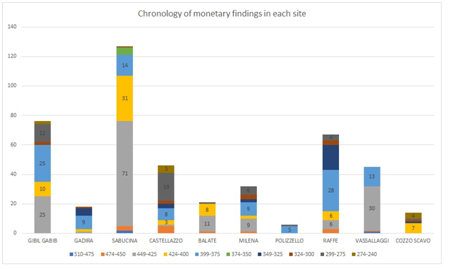

The second and third diagrams show the temporal distribution of coins. In chart 2, each column shows the presence of coins at each site for periods of 25 years. The count begins with the earliest recorded date of 510 (which corresponds to an Akragantine coin from 510-472 found in Vassallaggi) and ends with the latest recorded date of 240 (corresponding to one Syracusan coin from 269-240, found in Castellazzo).

Chart 2

Chronology of monetary findings in each site

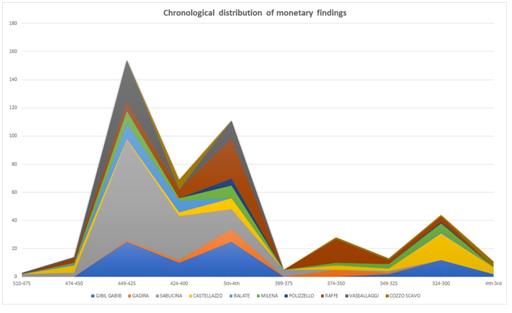

Graph 3 shows the chronological distribution of the findings more clearly. In this case, the periods are divided into 25 years as well, from 510 to 240.

Chart 3

Chronological distribution of monetary findings

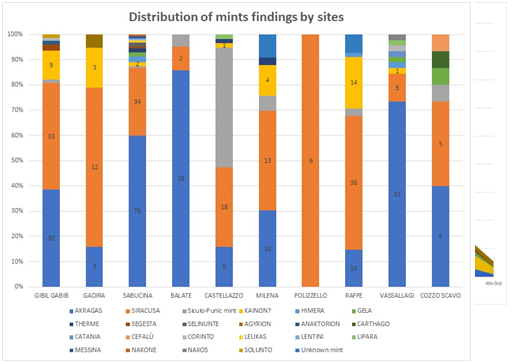

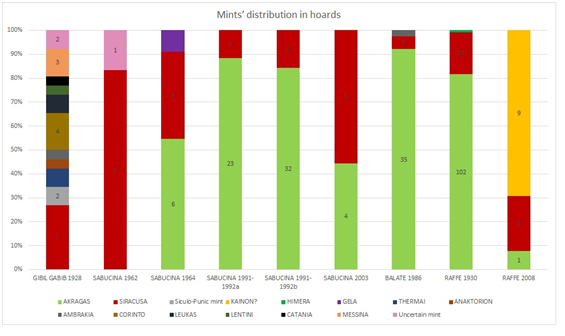

The next two charts (4 and 5) show the locations of the mints. In chart 4, the preponderance of the Akragantine and Syracusan mints is evident. Graph 5 shows the presence of mints in each hoard. The 1928 Gibil Gabib hoard contains the largest variety, with specimens from eleven mints.

Chart 4

Distribution of mints findings by sites

Chart 5

Mints’ distribution in hoards

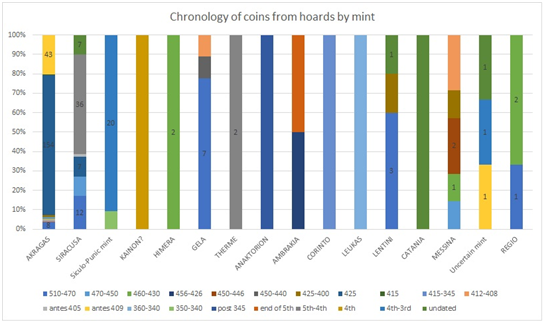

In chart 6, each column records a mint and the colours mark the time sequences. Here, instead of dividing the timeline into periods of 25 years, all recorded dates were considered.

Chart 6

Chronology of coins from hoards by mint

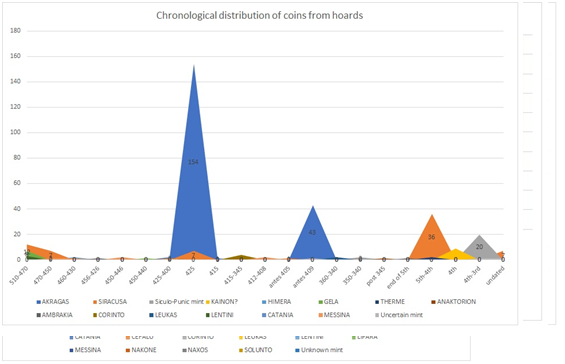

Graph 7 shows the distribution of coins. The highest concentration is recorded between 425 and 409, with a peak between the end of the 5th and the beginning of the 4th centuries.

Chart 7

Chronological distribution of coins from hoards

Analysis of monetary circulation in Sikania indicates the prevalence of coins from Akragas and Syracuse (charts 1 and 4). The presence of Punic coins and coins bearing the legend KAINON is also important. In general, the coins from this geographical area are made of bronze dating from the second half to the end of the 5th century, and from the second half of the 4th century (chart 3). Chart 2 shows the prevalence of coins from the last quarter of the 5th century at almost every site, and of coins from the first quarter of the 4th century at the sites of Gibil Gabib and Raffe, where a period of demographic and cultural growth took place according to archaeological contexts. The mints of Akragas and Syracuse are also represented in large numbers in the hoards (chart 5), with a prevalence of specimens from the second quarter of the 5th century and the beginning of the 4th century (charts 6 and 7).

Dealing with the history and significance of Siceliot emissions here would be a vast and complicated matter. It will, therefore, be enough to consider some aspects of the circulation of coins outside of the circumscribed asty range and their impact on indigenous communities.

The perception of the Greek monetary system by native populations in Southern Italy and Sicily has been a long-debated topic (Stazio, 1983a; Sole, 2015b). Recent studies (Caltabiano; Puglisi, 2004) have shown how, generally in the context of chorai, coins from the Siceliot poleis were rarely minted to meet the demands of a currency-enabled market. The problem of accepting the monetary system would thus not only be restricted to the indigenous people but would affect the entire “colonial” context of Sicily:

The constant variability in the location and the number of mints active in Sicily [...] compels one to wonder about the real function of currency issued on the island from the 6th century BCE to the Imperial age. The alternative is to identify this function in socioeconomic instances that see in the coin, based on Aristotelian thought, an instrument of social justice for the distribution of wealth, the payment of activities and services, fees, taxes, customs and tolls; or to mainly recognize in it a means of payment for the military expenses required by the policies of conquest, control and defence of territory [...] (Caltabiano; Puglisi, 2004, p. 335. Author’s translation).

A function that is mainly linked to commercial and military demands seems to be grounded in the numismatic evidence of the interior of the island where Akragas, Himera and Selinunte had expanded their chorai. Akragas, in the 5th century, was a very prosperous city mainly because of its agricultural economy (Diod. XIII, 81, 4-5). The polis minted heavy bronze coins bearing an eagle on the obverse and a crab on the reverse (Fig. 2). These coins spread mainly inside the chora, where a continuity of use is also documented after their official issuance (sometimes retaining its political value through countermarks). For this reason, some scholars consider them a “border issuance”, that is, coins issued in border cities (Caltabiano et al., 2006, p. 657), that are able to dialogue with those inhabiting this territory who primarily focused on agricultural activities. In this regard, we should recall that the Siceliot bronze coins used a peculiar unit of measurement common in the Greek world, the litra, whose fractions were calculated on the basis of silver to provide the same purchasing power and which probably originated in the Italian peninsula (Caltabiano et al., 2006, p. 656). The capillary diffusion of Akragantine bronze in Mesogeia can be explained by the ancient habit of native populations using metal as a bartering tool. In some hoards (Sabucina, 2003, Raffe, 1930 e Raffe, 2008 apudSole, 2012 – see below), arrowheads11 and coins were found together. This probably occurred because of the equivalence between the two metallic objects, due to the intrinsic value of the metal itself (Sole, 2015a, p. 269; 2015b, p. 780). The silver coins from the first half of the 5th century, on the other hand, are found mainly (but still in small quantities) in the hoards buried in early 4th century, showing thus a preference for bronze for business transactions and silver as metal to be stocked.

Figure 2

Heavy bronze coin from Akragas (onkia, ca. 406). Source: coinarchives.com (Gorny & Mosch Giessener Münzhandlung > Auction 265. Lot number: 74. Auction date: 14 October 2019)

From the end of the 5th century, the conflicts on Sicily were amplified mainly because of the politics of Dionysus I and the attacks of the Carthaginians. The island was populated by troops of mercenaries (Diod. XIV, 7), many of which settled in the inland of the chorai. According to some scholars, the Mesogeia assumed the aspect of a war frontier during this period (Sole, 2012, p. 340) because it was an intersection between the chorai of Syracuse, Himera and Akragas, and the Punic epicracy. The presence of coins in this area, mainly bronze ones, intensified, and coins from Carthage and Siculo-Punic mints began to circulate in parallel with the Greek ones.

A coin network: some case studies and hoards

To better understand the use of coinage and the perception of a monetary system in Mesogeia, it seems wise to observe the distribution of monetary findings inside and outside of the towns. Most of the coins were found in urban centres and, to a lesser extent, in sacred areas, whereas findings in the necropolises and near the walls are few. In sacred contexts, coins only assume the symbolic value of ex-voto at an early stage of contact (end of the 6th-beginning of 5th centuries), whereas it is difficult to determine their use in successive centuries. The same thing can be said for the necropolises (Sole, 2012, p. 323). Coins found in the context of the urban centre inform us mainly about their use in business transactions.

The data from Vassallaggi12 is fascinating. In its sacred area, built in the 6th century, coins were found in the buildings around the temenos and the temple. According to the interpretations, the oldest ones13 would have been used as votive offerings in the foundations of a service room connected to a cult. The more recent ones may, in my view, have a certain relevance to the productive and commercial functions of the structures around the temenos14 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3

Ortophoto of the sacred area at Vassallaggi archaeological site. Surrounding the small temple in antis (built in the 6th century) is a network of buildings that most likely had a productive and commercial function linked to the activities of the temple itself which welcomed the faithfuls.

A complete panorama of circulating coins is undoubtedly offered by Sabucina, in which a consistent numismatic documentation has been retrieved. Eight kilometres North-East from the city of Caltanissetta there are two calcarenite mountains, Sabucina and Capodarso, on the top of which two ancient cities were founded. The sides of the mountains that go down to the Salso River create a bottleneck in its course (Fig. 4), allowing full control of the passage. Salso is a long river connecting the northern and southern coasts of Sicily. It is for this reason that particularly Sabucina (inhabited from the ancient Eneolithic era until the beginning of the 4th century) had a significant strategic importance.

Figure 4

A 1950s picture of Salso River, Capodarso Bridge.

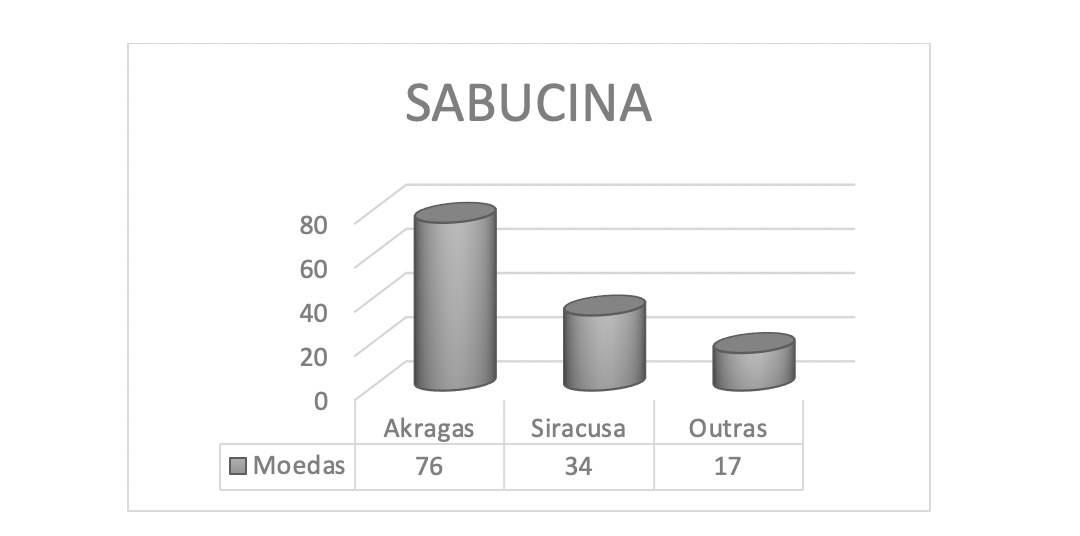

Sabucina is, so far, the site in Central Sicily in which the largest number of coins was found (chart 8), with the total of 219 coins. Among these, 90 coins come from five different hoards. Coins date from the beginning of the 5th until the second half of the 4th century and are predominantly bronze (only the oldest coin is silver).

Chart 8

Graphical representation of Sabucina’s monetary findings. Among the poleis represented in the numismatic documentation there are: Akragas (77); Syracuse (35); Segesta (1); Selinunte (2); Himera (3); Thermai (2); Messina (1); Lentini (1); Nakone (1); Gela (2); Siculo-Punic mints (1); Kainon (2); Leukas (1) (SOLE, 2012, p. 185-282

Archaeological research showed that the town in Sabucina reached its full development in the 5th century but was gradually abandoned during the 4th century (Miccichè, 2011, p. 89 ff.). Monetary evidence seems to confirm this data. In fact, the specimens dating from the end of the 5th and the beginning of the 4th centuries are in preponderant numbers. Among them, many heavy Akragas bronzes with the eagle / crab inscription, with or without countermarks, were found, while coins from the 4th century are few.

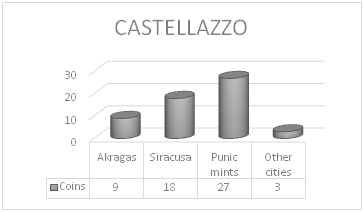

In cities that continued to thrive in the 4th century (Gadira, Gibil Gabib, Raffe, Castellazzo and Cozzo Scavo), monetary findings in sacred areas and necropolises are extremely scarce and are mainly concentrated in urban centres. The few coins found in Polizzello date from the early 4th century and suggest the presence of a small group, perhaps mercenaries, who temporarily could have occupied the place (Palermo, 2009, p. 311). In this period, mercenaries played indeed a significant role in the life of the towns in Central Sicily. Wars between Siceliots and Carthaginians turned the central area of the island into a place of transitions and negotiations. Castellazzo is the town where most numerous Siculo-Punic coins have been found.

Castellazzo Mountain is located North-East of Marianopoli15 and is on the shores of the Madonie Mountains. This site was inhabited from the Neolithic era until the 3rd century and was probably called Mytistraton, as numismatic evidence suggests: some coins bearing the legend MY, MYTIΣTPATΩN, MYTY were found in the town. Unfortunately, their provenience is only known through excavation reports since they were dispersed in antiquity market (see SOLE, 2012, p. 106, with bibliography).

The coins from Castellazzo are all bronze and date from the end of the 5th to the first half of the 3rd centuries. Coins from the end of the 4th to the beginning of the 3rd centuries are prevalent, and the Siculo-Punic coins are present in high numbers, as opposed to the other cities (Chart 9)

Chart 9

Graphical representation of the monetary findings of Castellazzo. Among the poleis represented in the numismatic documentation are Akragas (9); Syracuse (18); Siculo-Punic (27); Kainon (1); Lipara (1); Thermai (1); Mytistraton (unknown number) (Sole, 2012, p. 96-126).

In the south-East of Castellazzo, there is a small town in Cozzo Scavo (Santa Caterina Villarmosa). Archaeological evidence in this town points to the presence of a group of Campanian mercenaries who had intense trade with Carthaginians, between the 4th and 3rd centuries (Acquaro; Fariselli, 1997), but no coins have been found here. It would seem that the communities of mercenaries at Castellazzo and Cozzo Scavo could have kept contact during Hellenistic age, but both cities were destroyed and abandoned in the first half of the 3rd century. Diodorus Siculus (XXIII, 9, 3) reports that, during the first Punic war (264-241), Mytistraton was invaded by the Roman army twice (in 261 and in 259), because it was a Carthaginian phrourion. On the other hand, according to scholars (Acquaro; Fariselli, 1997, p. 9), Cozzo Scavo was invaded and destroyed by Pyrrhus, between 278 and 276. Nevertheless, it is safe to say that the current state of archaeological researches cannot provide a definitive conclusion about the chronology, which leads to the conclusion that it is not so improbable that the ending of the two towns was due to the same cause. It is then possible to assume that either the mercenaries in Cozzo Scavo left the place shortly after the turmoil caused by the Pyrrhus invasion in 278-277, and joined the Mytistraton mercenaries; or, at the time of the Roman invasion, the two cities joined battle and suffered the same fate in 259.

We can observe that the monetary findings mainly date from the second half of the 5th century: hoards were found in the whole area of Central Sicily (Sole, 2012) and are dated between the end of the 5th and the beginning of the 3rd centuries. We can distinguish two types of hoards: “emergency hoards” and “saving hoard”.

Saving hoards contain specimens with a particular intrinsic value in a wide chronological range – a symptom of the wish to collect and storage precious metal. Consequently, these hardly reflect a picture of monetary circulation from the moment they were hidden or lost. Hoards of Caltanissetta 1948 (Sole, 2012, p. 40 ff.), Balate 1986 (Sole, 2012, p. 68 ff.), Sabucina 1964 (Sole, 2012, p. 215 ff.), Gibil Gabib 1928 (Sole, 2012, p. 142 ff.), and Santa Caterina Villarmosa 1955 (Sole, 2012, p. 309 ff.) are considered saving hoards. The hoard of Caltanissetta only contained silver coins from Akragas, Camarina, Catane, and Gela, dating from 510-472 to 415-405. The hoard of Santa Caterina Villarmosa 1955 was also only composed of silver coins from various Siceliot poleis and Athens, dating from 510-472 to c. 420. The loss of the two hoards may therefore have happened in the second half of the 5th century. In the other two saving hoards listed above, along with the silver coins, there were bronze coins that perhaps were added right before hiding the money (Sole, 2012, p. 326).

Emergency hoards contain mainly coeval coins which were not necessarily of high intrinsic value and reflect the monetary circulation of the time when they were lost. We could imagine an individual, in a moment of imminent danger, that collected his finances for hiding, thinking he would recover them later. Emergency hoards found in Mesogeia contain especially heavy bronze coins from Akragas with or without countermarks (issued in the middle of the 5th century but still circulating in Central Sicily for their high intrinsic value), Syracuse (from Dionysus I emissions), and Sicilian and African Punic mints. They are: Raffe 1930 (Sole, 2012, p. 163 ff.), Sabucina 1962 (Sole, 2012, p. 214 ff.), Sabucina 1991-1992 (a) and 1991-1992 (b) (Sole, 2012, p. 218 ff.), Sabucina 2003 (Sole, 2012, p. 216 ff.). In the hoards of Raffe 1930 and Sabucina 2003, the coins were deposited with bronze objects and arrowheads, all weighing 2 grams, which had evidently lost their function as weapon to acquire a currency value. The two Sabucina hoards were found in the south-western off-wall sacred area within two cave environments intended for the ex-voto deposit. Except for those found in Sabucina, emergency hoards were interpreted as misthoi16 of mercenaries. The most recent emergency hoards are Raffe 2008 (Sole, 2012, p. 172 ff.) and Santa Caterina Villarmosa 2008 (Sole, 2012, p. 315 ff.), both lost between the end of the 4th and the beginning of the 3rd centuries. They contain mainly coins bearing the KAINON legend and Punic coins, and it is for this very reason they were interpreted as misthoi of mercenaries hired by the Carthaginians.

Conclusions

In the inner cities, specimens of the first Siceliot coins (late 6th century) are not present as mediators in the barters but are used mainly for their symbolic value. Nevertheless, we do find a few examples of this in indigenous contexts in the first half of the 5th century. It is possible to interpret this absence as a difficulty by the Sikan world in adopting coins, being such a controversial object in terms of symbolic meanings, as an interpreter of its own magical and sacred universe (see Florenzano, 2009, p. 19).

The shortage of coins until the middle of the 5th century reveals the distance of the Sikans from the idea of an economy ruled by weighted systems based on values which were probably unrelated to their culture. After all, using Polanyi’s words (1968, p. 179): «No one rule is universally valid, except for the very general, but no less significant, rule that money-uses are distributed between a multiplicity of different objects». It is probably because of a lack of this sense of understanding that Akragas, even at the beginning of the 5th century, did not have a strong currency comparable to the city’s achievements in the production of consumer goods and architectural forms. The first significant change comes shortly after the Ducetius revolt (Galvagno, 2000), where Akragas is decisively present using coins as a vehicle of power. For instance, the increased presence of Greek coins – especially the ones from Akragas – in Sabucina (chart 8) and generally in the interior is revealing. The coin in this case clearly plays the role of a transformative agent in this new phase of life of the Siceliot poleis, their chorai, and the cities involved in their policies. Trades and transactions need a common language, that is, a sign of a completed social transformation. Coins, as an aspect of political expression, were fully adopted in this territory thanks to the settlement of mercenaries in the 4th and 3rd centuries, who accumulated their misthoi and use sitos as a form of internal and external barter.

Mercenaries issued coins as minted money in the many cities founded or occupied by them, not only to make transactions possible, but also to convey their identity as political entities and citizens. That being said, it is essential to highlight that mercenaries “often come from the polis and in the polis they intend to return, so they do not stand as an alternative to membership; if they are away, it is by chance and for a possibly limited time” (Bettalli, 2006, p. 56).

references

ACQUARO, E.; FARISELLI, A. Cultura punica “di frontiera”. Alcune testimonianze da Cozzo Scavo (CL). OCNUS, v. 5, p. 9-32, 1997.

ALBANESE PROCELLI, Rosa Maria. Sicani, Siculi, Elimi. Forme di identità, modi di contatto e processi di trasformazione. Milano: Longanesi, 2003a.

ALBANESE PROCELLI, Rosa Maria. Produzione metallurgica di età protostorica nella Sicilia centro-occidentale. In CORRETTI, Alessandro (ed.). Atti delle quarte giornate internazionali di studi sull’area elima e la Sicilia occidentale nel contesto mediterraneo (Erice, 1-4 dicembre 2000). Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore, 2003b. v. 1, p. 11-28.

AMICO MEDICO, Giuseppe. La scoperta di Caulonia di Sicilia presso la città di San Cataldo. Ristampa integrale. [S.l.]: Cassa Rurale e Artigiana “G. Toniolo”, 1871.

ANELLO, Pietrina. Le popolazioni epicorie di Sicilia nella tradizione letteraria. In TUSA, Sebastiano (ed.). Prima Sicilia. Alle origini della società siciliana (Palermo, 18 ottobre 1997 – 22 dicembre 1998). Palermo: Ediprint, 1997. v. 2, p. 539-57.

ANTONACCIO, Carla M. Siculo-geometric and Sikels. In LOMAS, Kilian (ed.). Greek identity in the Western Mediterranean. Leiden: Brill, 2004, p. 55-81.

BETTALLI, Marco. Hoi ton Hellenon aporoi: i mercenari del mondo greco classico tra violenza, emarginazione e integrazione. In URSO, Gianpaolo (ed.). Terror et pavor. Violenza, intimidazione, clandestinità nel mondo antico. Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Cividale del Friuli, 22-24 settembre 2005). Pisa: ETS, 2006, p. 55-64.

CALTABIANO, Maria Caccamo; PUGLISI, Mariangela. Presenza e funzioni della moneta nelle chorai delle colonie greche della Sicilia: età arcaica e classica. In CENTRO INTERNAZIONALE DI STUDI NUMISMATICI. Presenza e funzioni della moneta nelle chorai delle colonie greche dall’Iberia al Mar Nero. Atti del XII Convegno organizzato dall’Università “Federico II” e dal centro Internazionale di Studi Numismatici. Napoli 16-17 giugno 2000. Roma: Istituto Italiano di Numismatica, 2004, p. 333-95.

CALTABIANO, Maria Caccamo; CASTRIZIO, Daniele; PUGLISI, Mariangela. Dinamiche economiche in Sicilia tra guerre e controllo del territorio. In MICHELINI, Chiara (ed.). Guerra e pace in Sicilia e nel Mediterraneo antico (VIII-III sec. a.C.): arte, prassi e teoria della pace e della guerra. Atti delle quinte giornate internazionali di studi sull’area elima e la Sicilia occidentale nel contesto mediterraneo (Erice, 12-15 ottobre 2003). Pisa: Ed. della Normale (Seminari e convegni; 7,2), 2006. v. 2, p. 655-73.

CAMPANA, Alberto. Sicilia (Bruttium?): Kainon (ca. 387-376 a.C.). Panorama Numismatico, v. 130, inserto v. 2, p. 309-20, 1999.

CUTRONI TUSA, Aldina. I ripostigli di bronzo e la loro funzione pre e paramonetale. In TUSA, Sebastiano (ed.). Prima Sicilia: alle origini della società siciliana. (Albergo dei Poveri, Palermo, 18 ottobre-22 dicembre, 1997). Palermo: Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e Ambientali e della Pubblica Istruzione; Palermo: Ediprint, 1997. v. 1, p. 567-78.

FLORENZANO, Maria Beatriz Borba. A origem das moedas. In FLORENZANO, Maria Beatriz Borba; VIANNA, Salvador Teixeira Werneck; CASTRO, Maurício Barros de (ed.). Faces da moeda. São Paulo: Olhares, 2009, p. 12-56.

FLORENZANO, Maria Beatriz Borba. Fontes sobre a origem da moeda: apresentação crítica. Revista do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, v. 1, n. 11, p. 201-11, 2001.

FLORENZANO, Maria Beatriz Borba. Cunhagem e circulação monetária na antiguidade clássica: dos tesouros monetários. Dédalo. Revista do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, v. 1, n. 26, p. 139-47, 1988.

FREDERICKSEN, Rune. Greek city walls of the Archaic period: 900-480 BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

GALLO, Luigi. La democrazia ateniese del IV sec. a.C. e la paga dei funzionari pubblici. Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, Classe di Lettere e Filosofia, serie 3, v. 14, n. 2, p. 395-440, 1984.

GALVAGNO, Emilio. Politica ed economia nella Sicilia greca. Roma: Carocci Editore, 2000.

GALVAGNO, Emilio. I Sicani: profilo storico. In GUZZONE, Carla (ed.). Sikania: tesori archeologici della Sicilia centro-meridionale (secoli XIII-VI a.C.). Catalogo della mostra. Wolfsburg-Hamburg, ottobre 2005-marzo 2006. Collaborazione di Marina Comgiu. Catania: Giuseppe Maimone, 2006, p. 25-31.

GAZZANO, Federica. Dalla lingua all’ethos: i Greci e l’idea del barbaro. In CAMPODONICO, Angelo; VACCAREZZA, Maria Silvia (ed.). Gli altri in noi. Filosofia dell’interculturalità. Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino Editore, 2009, p. 3-26.

GIARDINO, Claudio. La metallotecnica nella Sicilia pre-protostorica. In TUSA, Sebastiano (ed.). Prima Sicilia: alle origini della società siciliana. (Albergo dei Poveri, Palermo, 18 ottobre-22 dicembre, 1997). Palermo: Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e Ambientali e della Pubblica Istruzione; Palermo: Ediprint, 1997. v. 1, p. 405-14.

GRANDJEAN, Catherine. La monétarisation de l’astu et de la chôra des cités grecques (VIe s. av. N.È.-Ve s. de N.È.) en questions. Revue Belge de Numismatique et de Sigillographie, v. 161, p. 3-15, 2015.

GRIFFITH, Guy Thompson. The mercenaries of the Hellenistic world. Reprint of the first ed., 1935. Groningen: Bouma’s Boekhuis, 1968.

GUZZETTA, Giuseppe. Prototipi monetali sicelioti e interpretazioni puniche. In CONGIU, Marina; MICCICHÈ, Calogero; MODEO, Simona; SANTAGATI, Luigi (ed.). Greci e Punici in Sicilia tra V e IV secolo a.C. (Caltanissetta, 6-7 ottobre 2207). Caltanissetta: Salvatore Sciascia Editore, 2008, p. 149-172.

HANSEN, Mogens Herman; NIELSEN, Thomas Heine. An inventory of Archaic and Classical Greek poleis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

HOWGEGO, Christopher. La storia antica attraverso le monete. Translation by Lucia Travaini. Roma: Edizioni Quasar, 2002.

LO MONACO, Viviana. Redes de interação entre gregos e não-gregos: os frúria da hinterlândia da Sicília grega. 2018. Tese (Doutorado em Arqueologia) – Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2018. Available in: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/71/71131/tde-23112018-093434/pt-br.php. Last login on Jan. 7, 2020.

LO MONACO, Viviana. Phrourion: History and Archaeology of a Word. Revista História, v. 39, p. 1-20, 2020. Available in: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0101-90742020000100414&script=sci_arttext&tlng=em. Last login on Oct. 19, 2020.

MANGANARO, Giacomo. Città di Sicilia e santuari panellenici nel III e II sec. a.C. Historia, v. 13, p. 414-39, 1964.

MICCICHÈ, Calogero. Mesogheia. Archeologia e Storia della Sicilia centro-meridionale dal VII al IV sec. a.C. 2. ed. Caltanissetta: Sciascia Editore, 2011.

PALERMO, Dario. Cap. 6. L’acropoli di Polizzello fra l’Età del Bronzo e il VI séc. a.C.: problemi e prospettive. In PANVINI, Rosalba; GUZZONE, Carla; PALERMO, Dario (ed.). Polizzello. Scavi del 2004 nell’area del santuario arcaico dell’acropoli. Viterbo: BetaGamma, 2009, p. 297-313.

PANCUCCI, Domenico. I Sicani. In ANELLO, Pietrina; MARTORANA, Giuseppe; SAMMARTANO, Roberto (ed.). Ethne e religioni nella Sicilia antica. Roma: Giorgio Bretschneider, 2006, p. 107-19. Suppl. a Kokalos, v. 18.

POLANYI, Karl. Primitive, archaic, and modern economies: essays of Karl Polanyi. Edited by George Dalton. 2. ed. Boston: Beacon Press, 1968.

SANFILIPPO CHIARELLO, Giuseppe. Vassallaggi (CL): campagna di scavi 2003 nell’area del santuario urbano. Scuola di Specializzazione in Archeologia Classica “Paolo Orsi”. Catania, 2004-2005.

SOLE, Lavinia. La via dei metalli in Sicilia. Un contributo dai ripostigli per lo studio delle fonti di approvvigionamento. In PANVINI, Rosalba; GUZZONE, Carla; SOLE, Lavinia (ed.). Traffici, commerci e vie di distribuzione nel Mediterraneo tra protostoria e V secolo a.C. Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Gela 27-28-29 maggio 2009). Caltanissetta: [s.n.], 2009, p. 185-93.

SOLE, Lavinia. Gli Indigeni e la moneta. Rinvenimenti monetali e associazioni contestuali dai centri dell’entroterra siciliano. Caltanissetta: Salvatore Sciascia Editore, 2012.

SOLE, Lavinia. I Sicani nel IV secolo a.C.: osservazioni sui rinvenimenti monetali dall’ entroterra dela Sicilia. In PANVINI, Rosalba; CONGIU, Marina (ed.). Indigeni e Greci tra le valli dell’Himera e dell’Halykos. Atti del convegno. (Caltanissetta, Museo Archeologico Regionale, 15-17 giugno 2012). Palermo: Regione siciliana; Assessorato dei beni culturali e dell’identità siciliana, 2015a, p. 265-79.

SOLE, Lavinia. Coinage and Indigenous Populations in Central Sicily. In MILITELLO, Paolo Maria; ÖNIZ, Hakan (ed.). SOMA 2011. Proceedings of the 15th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology (University of Catania, 3-5 March 2011). Oxford: Archaeopress, 2015b. v. 2. p. 779-87. (BAR International Series; v. 2695/II)

STAZIO, Attilio. Monetazione greca e indigena nella Magna Grecia. In SCUOLA NORMALE SUPERIORE (Pisa); ÉCOLE FRANÇAISE DE ROME; CENTRE DE RECHERCHES d’Histoire Ancienne (Besançon). Modes de contacts et processus de transformation dans les sociétés anciennes. Actes du colloque de Cortone (24-30 mai 1981). Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore; Rome: École Française de Rome, 1983a, p. 963-78. (Publications de l’École française de Rome, v. 67)

STAZIO, Attilio. Considerazioni sulle prime forme di tesaurizzazione monetaria nell’Italia meridionale. In HACKENS, Tony; WEILLER, Raymond (ed.). Actes du 9ème Congrès International de Numismatique, Berne, septembre 1979. Louvaine-la-Neuve: Association Internationale des Numismates professionelles, 1983b, p. 52-69.

TRECCANI. Enciclopedia on-line. Available in: http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ . Last login on July 8, 2018.

TRUNDLE, Matthew. Greek mercenaries. From the late Archaic period to Alexandre. London: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2004.

WINTER, Fredericksen E. Greek fortifications. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1971.

Notes